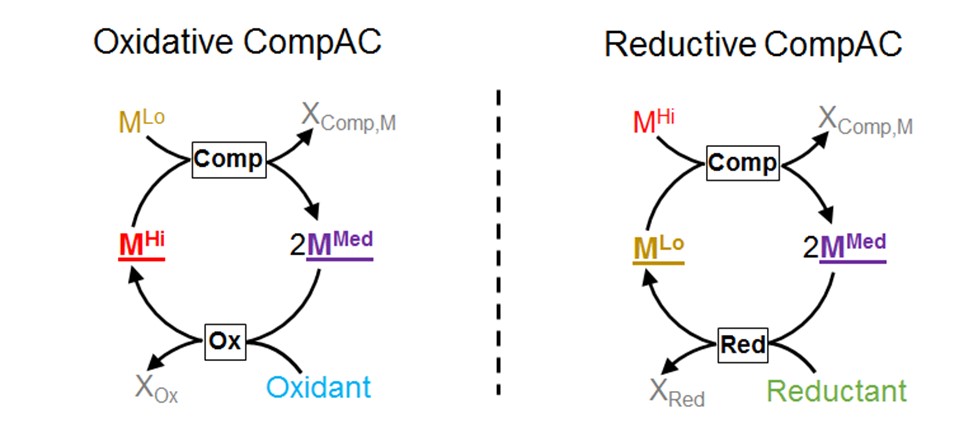

A CompAC is a Comproportionation-based Autocatlytic Cycle. It is formed by joining a comproportionation reaction with an auxiliary oxidative (left) or reduction (right) reaction that connects outputs with inputs. Each time the comproportionation reaction occurs, at least 2 intermediate-state species are generated. In this way, a CompAC forms an autocatalytic loop of reactions that amplifies the intermediate-oxidation-state species and, indirectly, the other species that form the cycle.

Image from Peng et al., 2023.

Why are CompACs unique?

One of the main attributes that distinguishes living chemical systems from non-living chemical systems is that life is chock full of autocatalytic relationships. Cells divide and multiply, populations grow, and species compete for and share resources in ecosystems. All of the features that make these systems so dynamic and responsive are underpinned by autocatalytic relationships, where living systems can use available energy in the environment to make copies of itself.

Research into the origins of life runs into a problem of figuring out where and how the first autocatalytic relationships arose. Nearly all of the autocatalytic relationships in living systems are based on organic compounds- very specific and relatively complex molecules that contain carbon. Despite decades of research, it has been difficult to create chemical circumstances (even in a highly controlled environment like a laboratory) where one may expect organic compounds to form an autocatalytic cycle on its own.

This difficulty has led researchers to look beyond organic carbon for any general chemical system that can support naturally-emerging autocatalysis. The idea is that even if an autocatalytic system is inorganic (i.e., running on atoms and molecules that are not based on reduced carbon), it should still exhibit many of the same functional characteristics of living systems. Perhaps life even ‘grew out of’ these inorganic beginnings, as organic compounds afforded degrees of specificity, stability, reliability or versatility that inorganic compounds did not.

Our interest in CompACs is to outline a general strategy for finding a variety of autocatalytic systems that can be used to create complex phenomena from the smallest and simplest array of starting reactions. We need a general strategy because finding autocatalytic relationships in a given set of reactions is a kind of technical challenge called NP-complete. This means that you must comprehensively search all of the combinations of reactions in a system and test each one to see if it has the right stoichiometry that is autocatalytic; there is no algorithmic shortcut or simplifying calculation you can make to know how many such autocatalytic relationships are waiting to be found in the set. So if you have a list of thousands of reactions that can occur in geochemistry or cosmochemistry, the total number of possible sets you have to test is so big that it’s difficult for even the fastest computer to test all of the possibilities. NP-complete also means that it’s extremely difficult to know if running the search program longer will yield more results, or if adding a new reaction will generate new autocatalytic sets.

CompACs exploit a technicality that somewhat offsets the NP-complete nature of the problem because a specific kind of chemical reaction, comproportionation, creates the ‘splitting step’ of the autocatalytic cycle. By searching for comproportionation reactions, and by manually searching for auxiliary reactions that connect reaction outputs with reaction inputs, we were able to synthesize a list of autocatalytic cycles that lead to CompACs. In so doing, the CompACs are a list of known, demonstrated reactions that ought to have the capacity to lead to autocatalytic relationships.